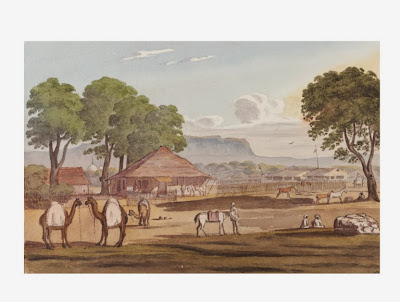

Panwell Inn.

From the Victoria & Albert Collection by Sir Charles Harcourt Chambers (1824-28)

(click on image for larger version)

Recently a copy of a water colour by Sir Charles Harcourt Chambers of the Panwell Tavern from the Victoria and Albert Museum was posted on Facebook that caught my attention. Although not the finest or most historical of the millions of buildings in India it is one which generations of travellers from Bombay to Poona and the interior will have been familiar with.

My own great great and great great great grandfathers, Bombay Artillery Officers and their families must have known it well as the travelled up and down between Mumbai and Pune, because Panvel was the first stage or last stop on the journey.

Map showing the location of Panwell from Google Earth.

(click on image for larger version)

Although Panwell (known) today as Panvel was only 21 miles as the Seagull flies, in 1817 it was a frontier town, and the East India Company only had limited control of the area. Captain James Barton by gt gt gt grandfather, appears to have been stationed in Bassein at this time, a little to the north.

In late 1816 the Pindarees were raiding down the Ghats seizing silk. They were heading north. Did James see them pass the ramparts?

"The Bombay Courier says, that the communication between the Seroor and Poonah, and the latter place and Panwell, had for a fortnight been unsafe without a guard. ' "Numerous Mahratta families have within these few days sought for refuge in the islands of Caranja and Salsette. The Principle object of the Pindarees in entering the Concan was to seize a large quantity of kincob (silks) which was exported from Bombay to Chowal for the interior. This they succeeded in. It is their intention to sweep the coast as far as Surat." [1]

James Barton was tasked with cutting off access down the Ghats to the north. A more senior officer, Colonel Prother was sent with a column to attempt to drive the Mahrattas from the forts lining the crest of the Ghats to the south of the Poona Road. It was while I was researching these subsidiary campaigns, that I came across the following fascinating account of Panwell in a diary of an at present anonymous Bombay Artillery Officer in the British Library.

"

Tuesday Jan 13. [1818]

"Embarked along with Osborne [2]

in a Bunder Boat having sent off the Detachment

with Declezean [3]

an hour before -- We came up with them about half way &

arrived at Panwell about 1/2 past 4 the afternoon -- after disembarking the

Detachment getting Baggage etc. on shore we dine along with Mr Walker the

Officer of the port, at the Tavern -- This would pass for a very paltry inn in

England, nevertheless we got a very excellent dinner at a pretty moderate

charge from Don Lewis & he is very much deserves to be encouraged as such

an Establishment at a place generally (inhabited?), is a very great

convenience.

We were all busily employed this day in getting the carts & gun

carriage from the Boats, mounting guns & arranging stores.

Employed partly as the day before, & also in cutting fuzes, & preparing everything for a march-- The draught cattle arrived and I received

instructions to move on as soon as I was able-- In the evening rode out with

the others -- Panwell is a considerable village lately ceded to us by the

Peishwa chiefly inhabited by Musselmen, & one of the Chief Commercial

inlets to the Deccan. Boats come up within half or a 1/4 of a mile of it but the landing place is bad-- there is plenty of water in Tanks, but not particularly good.

I had a parade in the pro(?) with bullocks, & I did not intend to start

until next day, as the whole of the cattle had not arrived; but about midday

there arrived instructions to move that evening to Babenas, about half way on

the road to Chouken -- My detachment consists of 1 Serg't & 46 rank & file, 3 Tindals & 36 Lascars, & Mr Walker the officer stationed at Panwell with 30 Sepoys was placed under my orders. I had under my charge 2, 6 pdrs, 2 mortars, 8 inch, light 5 inch howitzers with a considerable quantity of ammunition & Horses, about 350 bullock loads, & 6 carts -- We marched from Panwell a little before 4 in the evening." [4]

Just one month later in February 1818 George Fitzclarence, 1st Earl of Munster travelled down the Ghats in the opposite direction, and like our anonymous artillery officer approved of the food served in the inn. He had been in Poona, and had passed within sight of forts in the Ghats still held by hostile Mahrattas.

"I had gone through so much fatigue and personal exertion, that I was quite unwell when I reached the bottom; and, lying down in my palanquin, was taken up by the hummalls(the Persian word) as they here call the bearers of Calcutta, the cahars of Hindoostan, and the bhoeys of Madras and the Dekhun, and never opened my eyes till called by Colonel Osborne in a little hovel dignified by the name of an inn,at Panwell, the village at which officers generally land from Bombay on their route to the Dekhun.

I found a boat belonging to the superintendant of the marine ready for me, and that the tide would answer at nine; and having dressed, and partaken of a splendid breakfast, I walked to the boat, which was very comfortable, and larger than the row boats on the Ganges. Panwell is situated on an inlet of the sea, which takes its name from the town; and, after a passage down of about ten miles, I reached the open harbour, of which the view was beautiful." [6]

The Earl of Munster has left a most interesting account of his travels that is available on Google Books, covering his entire journey across the war torn Mahratta districts. He was travelling with the HEIC forces engaged in the campaigns going on at the time, and is most interesting on the less military aspects of that campaign.

As so often in war, the disruption caused to civilians, gave diseases huge opportunities to develop and spread. Cholera is thought to have been present in the Indian population in a relatively mild form in the Deccan for several hundred years before 1817.

At about this time it mutated into a far more dangerous disease. It got into the advancing HEIC army as well the population, killing far more soldiers and civilians than the war itself.

Although there are few direct reports of refugees in British accounts, besides the fleeing Pindarees and Mahratta forces, it is highly probable that entire communities were also on the road fleeing the advancing HEIC forces. These people deprived of food and shelter, mixed with other nearby populations creating the ideal opportunity for Cholera to spread.

An epidemic was soon underway that would eventually spread across the Middle East and reach as far as the industrial heartlands of the English Midlands where it would kill thousands of working families.

Panwell was on one of the major routes from the war zone to the coast, and it not surprising that Cholera soon arrived in the district. In January 1819 readers of the Morning Chronicle will have read the following account of events in far away places, in their morning papers, little imagining that this outbreak would eventually reach as far away as London. The report is referring to events during the previous summer of 1817.

"

Bombay. — A report of the Cholera Morbus having appeared at Panwell, reached the Presidency on Thursday, when a Medical Gentleman, with numerous assistants, was despatched to render the sufferers all the necessary aid, and to report on it; since which we have been informed, it has made its appearance in Bombay, though not attended with such violent symptoms as at other stations ; yet we understand that some deaths have occurred, We have, however, but little anxiety of its spreading to any degree, as measures have been taken by the Medical Board to ensure the most prompt assistance. Since the foregoing was written, we have been favoured with a perusal of a letter from Tannah, on the same subject, which mentions the casualties at Panwell as amounting to thirteen in all, among which is a Conductor of Stores, Mr.Llewellyn the Medical Gentleman who went from this to Panwell on Thursday, has we understand been fortunate in his practice, and the most beneficial results have already taken place from his exertions; the village of Bellapoor has been also visited by this malady, and a few casualties have occurred, but ample- supplies of medicine have been forwarded to that place and Tullijah. Connected with this subject we are sorry to state, that with a view to create alarm, in the Tannah district, some evil disposed persons had caused two Buffaloes to be painted in an extraordinary manner, and had sent them from village to village by means of the Haziree Bigaries, and the prevalent idea is that wherever these animals are gone, there the disease will follow; the Buffaloes have however been seized, and we are informed will be sold by public auction, and we treat the reward of 300 rupees that has been offered, will lead to the apprehension of the offenders. Our last letters from Poonah mention that this disease still continues in that city, and the deaths among the lower classes have been as many as thirty and forty a day.

Walter Hamilton writing in 1828, at about the time that Chambers had painted his watercolour was less charitable about Panwell inn.

"PANWELL.—A town in the province of Aurungabad, situated on the river Pan, to which the tide flows up several miles from the harbour; but during the prevalence of easterly winds, the passage to Bombay, from which it is distant twenty-one miles E., is tedious and uncertain; lat. 18° 59' N., Lon. 73° 15 E. This place is extensive, and being eligibly situated for business, carries on a considerable commerce, although it stands in the midst of a salt morass. Panwell is the grand ferry to Bombay, and contains the rare convenience of an inn,although not of the first quality.[8]

"

The inn remained in use for many years. In 1840 it was recorded that a wedding took place of the widow of a former innkeeper.

"— At Bombay, Mr. Robert Maidment, to Helen, relict of the late Mr. J. W. Ward, inn-keeper at Panwell," [9]

In the same magazine it is recorded that the

"HC Iron Steamer Satellite" was sailing to Panwell from Bombay. Perhaps this was a response to the delays formerly caused by the easterly winds.

In 1847 it appears that a more formal and regular steamer route was being set up.

"The Bombay Steam Navigation Company has contracted with government to carry the Calcutta, Madras, and Deccan mails from Panwell, a distance of miles for £50. a mouth. Two light steamers are now being built on purpose at Bombay, and will, it is expected, be in operation by October."

Cholera remained at large in the Deccan for many years, although in a less virulent state than before. However from time to time it burst out with renewed strength. Outbreaks occurred in 1845 in Panwell and the surrounding districts, leading to fears that it would reach Bombay.

The route from Panwell left the village through marshy tidal flats before climbing up into the Ghats. The Victoria & Albert collection includes a second watercolour by Chambers showing this road.

Panwell Bunder by Chambers.

By the 1840's the route down the Ghats was becoming increasingly important for commerce. Britain's steam driven cotton mills was importing many thousands of tonnes of cotton annually, and India was being overtaken as the main source of supply by America which grew better quality cotton, and which had better quality roads. Efforts were being made in increase production, and to improve the quality of cotton grown as far away as Dharwar. However the state of the roads was adding to the cost of the transport required to bring it to the coast.

Some of the readers of the Northampton Mercury on Saturday 7th of July 1849 will have read the following report: with interest -

"The East India Company took possession of the Western Dekkan on the overthrow of the Mahratta empire 1818, now thirty years ago. The extent of made road," says Mr. Williamson, " along the great trunk lines of communication does not (exclusive of cross roads) exceed 350 miles, and these are very ill furnished with cross lines of communication." This statement however, though adduced to prove the negligence of the ruling powers, is, truth, far too favorable, if by the term "made road" is to be understood, as in Europe, a road bridged, drained, and covered with broken stones, so as to be practicable throughout for wheel carriages at all seasons. For this is true of very little more than the seventy miles of road from Panwell to Poona, and even this is so bad that nobody travels upon it private carriage. Sir Thomas M'Mahon, when Commander-in-Chief, had his carriage rolled over an unguarded precipice and broken to pieces. The other roads are either without regular bridges or culverts, or are not covered with broken stone; and in no other country or presidency would they be dignified with the title of a road. The Poona, or Bhore road, and another of greater length, but not quite practicable throughout all seasons, over the Thul Ghaut, are the only two tolerable passages across the Western Ghauts, and they receive the produce of country 300 miles long by 250 broad.

Wheel carriages can make their way on the Thul road without checks only during the fair season. By far the larger share of the traffic on both is carried on upon the backs of bullocks, ponies, and camels, but especially the former. The cotton stuffed into packs of about 125 1bs. each, and a pair of these form the load of a bullock. The animals travel in droves, from 100 to 1,000, or even more, under the conduct of the Brinjarries, to whom in many cases they belong, and in whose hands is the carrying trade of the country. Under ordinary circumstances, these Brinjarry bullocks pick up the cotton from the various villages at which it collected, traverse the open country, along routes regulated by the bargains made with the farmers of the transit duties, and often, therefore, very circuitous, until they reach the great cotton depots, or the trunk lines of the trackway, by which they descend the Ghauts, and discharge their loads at the sea-shore. This done, they either take return loads of piece goods, or other wares, or proceed to the Pans to to take salt. In fair weather, when forage and water are tolerably abundant, and the means of securing a return load easy, this mode of conveyance, though expensive and injurious to the cotton, is not ruinously so. It is, however, liable to, and frequently suffers, very serious disasters. Dr. Royle, judging from the results of the experimental cotton farms in Guzerat, the Dekkan, Khandeish, and Dharwar, established 1829, strongly of this opinion. The produce these farms, though Injured the cleansing, was worth from 6d 3/4. to 9d 1/2. per lb. The cotton harvest takes place in the interior somewhat earlier than near the sea. but everywhere the shortness of the period for ripening, conveying, and shipping the crop, is a serious evil. The wool does not reach the local market before February, and is not cleansed before April. It therefore work of difficulty to bring the crop into Bombay before the setting in of the rains early in June. The pack bullock does not travel,even when in motion, above six and a quarter miles a day, and from lameness or disease is often stopped for days together. From Kamgaon and Oomrawattee, the principal cotton marts, about sixty days are required to convey the crop to the sea. The hot season immediately precedes the monsoon. To avoid the latter, the bullocks are urged under heavy loads at their greatest speed, at a season when water and forage are least abundant, rather, are very scarce indeed, especially near the sea. The bullock is a slight animal, and quite incapable either of carrying an overload, or of travelling without proper supply of food and water. The droves descend the Ghauts in thousands, and even tens of thousands, drove after drove, pushing on through dense clouds of the minute volcanic dust of that district. The wells are few and low, made by the old Hindoo and Mussulman princes, and seldom repaired by us. At no season could they supply the wants of such numbers. The animals fall and die in scores from drought and fatigue, and their carcases are rolled to the road side. At first their loads are distributed over the others, but this resource soon fails; and after time the packs of cotton are rolled into the enclosure of some neighbouring village, there to take their chance of dirt, damp, or pillage, until the Brinjarries can return and take them up. The mortality of pack bullocks upon the Ghauts estimated at ten per cent, above that in the plain country, and near the salt pans it is much higher. Hundreds of their carcases," writes Mr. Fenwick are to be met with just previous to the monsoon, strewed along the paths they have traversed." When the droves are caught by the monsoon, the consequences are even more fatal. The trackways become heavy and impassable. The cotton absorbs moisture like a sponge, and, becoming double its usual weight, crushes the bullock to the ground. The produce is of course utterly spoiled. The enormous extent of this bullock traffic may be conceived from the fact, that a good cotton crop in the Oorarawattee districts alone, loads about 220,000 bullocks; of which about 20,000 find their way to Muzapoor to be conveyed by the Ganges to Calcutta —the remainder travel westward to Bombay. Some varieties ripen earlier than others ; and Dr. Royle is of opinion, that the crops in general might be brought forward by irrigation, so as to allow a longer time for the transit. But the grand remedy is a good road. The adventures of the cotton are not yet concluded. These two roads terminate, the Bhore upon Panwell, the Thul upon Kusseylee and Kolsette. Panwell is upon a tide river, which falls into Bombay harbour. The wind, during and for some time previous to the monsoon, blows steadily from Bombay; find the native boats (the unpressed cotton piled several feet above their decks) make the passage with great delay and damage from the wind and rain. Panwell is a wretched place, in which the cholera is frequently raging, and which offers little accommodation, either for shipping the cotton, or housing such of it as may arrive after the commencement of the monsoon. The terminations of the Thul road are upon a narrow arm of the sea, separating Salsette from the main land, and flowing into the top of Bombay harbour. [11]

Panwell Mosque drawn circa 1809 by William Westall,

and later engraved for the Naval Chronicle.

In 1856 my great great grandfather marched down the Ghats from Poona with his comrades to take part in the Persian Expedition, and once more back up the route on his way to Ahmednugger in 1858 on his return to take part in the Indian Mutiny.

Sadly, although but that time he had access to a camera, and took pictures of the head of the Ghats on his way to Poona, either the inn had gone, or it was no longer significant enough to justify making a picture of.

Did he ever stop at the inn?

Panvel today has become a commuter suburb of Mumbai, and a major town. The town plan appears to have been extensively redeveloped since 1817, so that I am unable to locate the old centre by inspection of Google Earth. Sadly I am unable to work out exactly where the inn was located, although presumably it was close to the main mosque that was such a feature of the village in early days.

I would be very grateful if any body who lives in Panvel today can help me locate the site of the inn. I would also like to find out what the modern name of the following two places are Babenas, about half way on the road to Chouken" and where they are.

I can be contacted on balmer.nicholas@gmail.com

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Google Books, the British Newspaper Archive and the V&A without which this article could not have been written.

[1] Exeter Flying Post Thursday 29 May 1817

[2] Probably Henry Lowry Osborne, born 22 July 1797. Addiscombe 1813-14. Lieutenant Fireworker. 3rd September 1815, Lieutenant 1 September 1818.

>Died 29 August 1819 at Bombay. Spring.

[3] Probably Marcus Claudius Decluzean, b. 1 Jan. 1799. Addiscombe 1814-1816, Lieutenant Fireworker 27 September 1817, Lieutenant 1st September 1818, Captain

28 September 1827, Married 13 Dec 1839. Retired 17th September 1850. Died 30 May 1881 at Baden. From Spring.

[4]From British Library Asian Collection, MSS Eur C418 Diary of a Bombay Artillery Officer 1818

[5] George Augustus Frederick Fitzclarence First Earl of Munster. George was born illegitimately on 29 January 1794. He was the son of King William IV and Dorothea Bland. He married Mary Wyndham in October 1819. He died on 20 March 1842 at age 48 having committed suicide.

[6]Journal of a route across India, through Egypt, to England, in the latter ... By George Augustus Frederick Fitzclarence Munster (1st Earl of)

[7] Morning Post Wednesday 06 January 1819 courtesy of the British Newspaper Archive.

[8]The East Indian Gazetteer: Containing Particular Descriptions of ..., Volume 1. Walter Hamilton.

[9] Leicester Journal Friday 06 August 1847

[10] The Asiatic journal and monthly register for British and foreign ..., Volume 33

[11] Northampton Mercury Saturday 7th of July 1849.